History of the Labrador Retriever and the Golden Retriever

By Mike Short

Created by combining, and fact checking where possible, several online sources*.

(Click on photos to enlarge them)

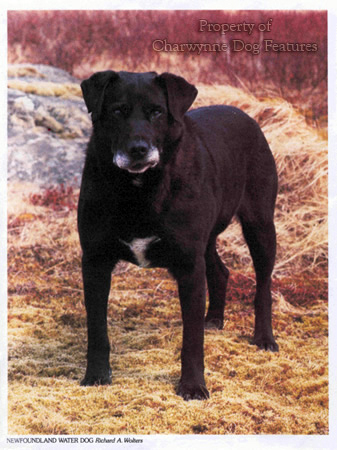

The St. John’s Water Dog otherwise known as the Lesser Newfoundland is believed to be the ancestor of the modern Labrador Retriever, the Golden Retriever, and the Chesapeake Bay Retriever.

St John’s is the capitol of the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador, it is on the Avalon peninsula on the island of Newfoundland at the most Easterly point of North America.

Both the Labrador and the bigger Newfoundland dog originated from the St. John’s Water Dog, both having webbed feet. The Labrador came from dogs that were selected for speed in the water being slighter and having a shorter coat. The Newfoundland, and the less well known Landseer, came from dogs selected for strength and were used for work such as pulling carts and water rescue, those breeds were possibly crossed with Mastiffs to increase strength.

In early days the island was inhabited by the Beothuk people (called Skrælings by the Vikings) whose ancestors, the “Dorset Culture”, had migrated from Hudson Bay further North. The Beothuk were not known to mix with the Europeans nor were they known to keep dogs unlike the Innu Inuit from the area to the North-West known as Labrador.

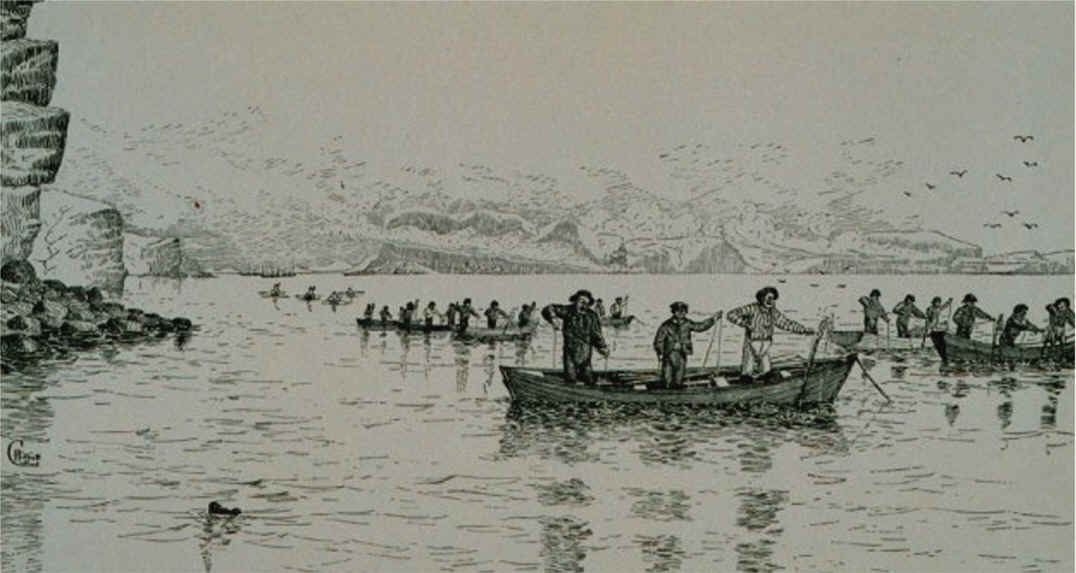

The line drawing shows indigenous people fishing along with a medium size dog. The dog does not particularly resemble a “sled dog” or Esquimaux dog or Husky as we know them today. Note that it does not have any white markings and doesn’t resemble the Newfoundland breed we know today.

However research did not reveal any historical evidence of indigenous people actually using dogs for fishing and nothing could be found about dogs in Newfoundland before the arrival of European fishing fleets in the 1500’s.

The lack of documentation is not surprising because back in the 16th and 17th centuries literacy was much less common than it is today. Also the visitors used diverse languages and were primarily there to work in the harsh conditions they encountered.

Starting around 1500 AD fishers from Portugal, the Basque country, Spain, France, England, and Ireland visited the “Grand Banks” off the Newfoundland shores for the plentiful cod catches, some 100 years before the journey of the Mayflower.

The French, Spanish and Portuguese fishing fleets worked on the Grand Banks and other banks out to sea, where fish were always available. They salted their cod on board ship and it was not dried until brought to Europe.

The fishers would put out in a Dory and return to the ship with their catch.

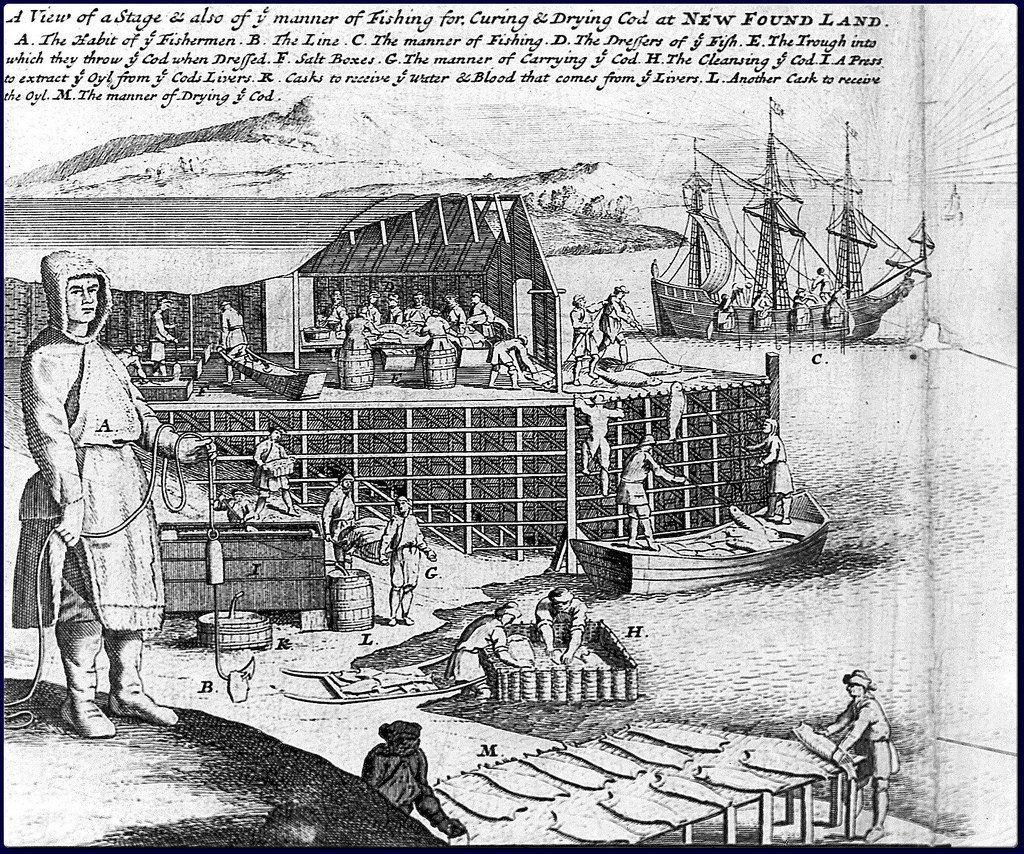

The English, who arrived a little later when their local fisheries no longer kept up with demand, concentrated on fishing inshore where the fish were seasonal. These fishers used small boats and returned to shore every day.

They developed a system of light salting, washing and drying onshore which became very popular because the fish could remain edible for years.

Many of their coastal sites gradually developed into settlements, notably St. John’s, now the provincial capital. The English fought with the French, as always.

In 1585 the Portuguese fishing fleet was raided by the English, who were at war with Portugal being part of the Kingdom of Spain. Led by Sir Bernard Drake, the raid was a disaster for the Portuguese, who didn’t send a fishing fleet the year after. In the late 1500’s the Spanish and Portuguese fisheries were terminated, mainly as a result of the failure of the Spanish Armada.

Following that the English and French shared the fishery every summer. In 1825 the British declared Newfoundland a colony. In 1904 the French agreed to relinquish it to the Newfoundland residents.

No doubt the fishers brought their working dogs with them from Europe. There were several European breeds at the time that were adept in the water, such as the Barbet, Spaniel, Portuguese Water Dog, and even Poodle. Those dogs will have been further bred as working dogs to help with fishing, maybe cross-breeding with native dogs to help withstand the harsh local conditions.

It is known that St. John’s dogs were imported to England in the early 1800’s which means that the breed had some 300 years to develop in Newfoundland.

The drawing of a St. John’s dated 1819 titled “Chien de terre neuve” looks remarkably like the dog with the Inuit fishing couple, especially the snout although the ears are more floppy. It has the beaver tail seen in most modern Labradors and also has small white boots.

Newfoundland itself went through many changes in that 300 years. The Portuguese, Basque, French, English and Irish were joined by early immigrants who found their way North from what is now the United States.

There was even a time when the infamous and very successful pirate Peter Easton made an inlet in Newfoundland his headquarters.

The St John’s dogs preferred by fishers were the smaller ones with shorter hair that later became known as the lesser Newfoundland. Their coat being dense and oily it repelled water and being short didn’t carry much ice when the dogs came out of the cold water. They were very adept at swimming and were as at home in the water as they were on land being used for dragging nets and retrieving fish that escaped the hooks. They were also known for their incredible sense of smell. The dogs were able to withstand harsh conditions with extremely cold and rough seas.

Because St. John’s dogs were bred for function not form, their appearance varied. They were stocky, medium-sized dogs with fur that could be long or short, smooth or feathered. In time black and white became common, and many could be recognized by their “tuxedo”, white boots, and muzzle.

Some settlers will have left the main fishing ports and headed up the coast, some will have taken dogs with them to help eek out a living throughout the seasons.

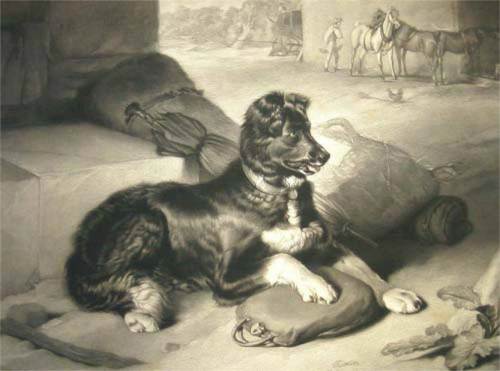

The painted lithograph of Cora by Edwin Landseer is of a dog that looks somewhat like a Labrador but with the typical markings of a St. Johns with the white muzzle, tuxedo, and boots. Cora may have been what became the Landseer breed that was mainly developed in the Netherlands. These markings are rarely seen in the modern Labrador, although they can appear in Labrador crosses, and can still be seen today in examples of the larger Newfoundland and Landseer breeds.

Through selection and inter-breeding the St John’s diverged into two breeds, the lesser Newfoundland and the Newfoundland which itself split into the Newfoundland and the Landseer.

The four following photos are the most recent of St. John’s Water Dogs (Lesser Newfoundland) before they became extinct in the 1980’s. Notice that the ears have become larger and more floppy and the white tuxedo and boots are smaller but still in evidence.

They are sturdy dogs with a barrel chest and a wide stance, as seen in English Labradors.

Last St. John's Water Dogs

St. John's Water Dog with small ears

Last of the old Newfoundland Water Dogs

Last St. John's Water Dog puppy

Eventually, it became very hard to own dogs in Newfoundland. In the nineteenth century, in order to promote sheep farming, the Canadian government instituted high taxes for new dog owners. England also had tough practices for dogs as they were often put into extended quarantine before being released to their owners. Both of these factors contributed to the extinction of the St. John’s Water Dog.

Today there are statues of the Newfoundland dogs in St. John’s Harbourside Park. Google Street View

The name Labrador was first used in England when St. John’s Water Dogs were imported from Newfoundland in the early 1800’s.

But for the 200 or more years before that Newfoundland settlers from Portugal, Basque Country, Spain, France, Britain, and Ireland had bred working dogs to help with fishing.

It is difficult to say whether the dogs were taken to Newfoundland by the fishers or the dogs were local to that area or a combination of both.

European fishers would spend the summer fishing and would then sail their salted fish to places like Poole on the South coast of England. They would bring back dogs from Newfoundland and often showed off the dogs’ water skills to the locals, who might have bought some from the fishers.

One Englishman who kept St John’s dogs was the 2nd Earl of Malmesbury (James Harris), who lived at Hurn Court (a.k.a. Heron Court) near Poole. As early as 1809 he had a St. John’s dog that joined him on shooting expeditions, and he and his descendants became avid breeders of the dogs, importing new animals from Newfoundland to keep the bloodline going. The Earl bred St John’s dogs to be used to retrieve water fowl during shoots on his estate.

It was he, the 2nd Earl of Malmesbury, who started the name “Labrador” which is to the North of Newfoundland, presumably to differentiate it from the bigger Newfoundland breed. His son the 3rd Earl continued the breeding.

The region of Labrador was named after a Portuguese explorer, but it’s also possible the dogs were named from the Portuguese for worker ‘lavradore’.

The dogs taken to the United Kingdom were initially used by hunters as working dogs to retrieve water fowl and were almost certainly cross-bred with other British hunting dogs. However they soon became popular as pets because they were friendly, affectionate, intelligent, and hard working.

In the 1830’s the Scottish 10th Earl of Home (Alexander Home, pronounced Hume), along with his nephews the 5th Duke of Buccleuch (Walter Scott) and Lord John Scott also imported St John’s dogs for work with wildfowl shoots.

The 6th Duke of Buccleuch (William Scott) continued his fathers work breeding the dogs keeping them as true to breed as possible. The Buccleuch gundogs kennels are still active today

In 1836 Colonel Hawker, an avid hunter who lived in Longparish in Hampshire, wrote “lost my beautiful Newfoundland dog to distemper”.

The 11th Earl of Home (Cospatrick Douglas-Home) owned a St John’s dog called Nell who is in what is believed to be the oldest known photo of the breed in 1867, at age 11.

In 1885 the 5th Duke of Buccleuch attended a shoot at Hurn Court and discovered that the dogs bred there by the 3rd Earl of Malmesbury were of the same breed as his. The Earl gave the Duke a pair of males for breeding that were the offspring of Tramp of Malmesbury and June of Malmesbury who were both born in 1878.

Those dogs were named ‘Buccleuch Ned’ and ‘Buccleuch Avon’ and were bred with females from the Buccleuch’s own St John’s bloodline to produce what is considered the ancestors of all of the modern breed. ‘Avon’ was mated with ‘Gip of Buccleuch”.

In the following photo notice the facial markings on some of the dogs.

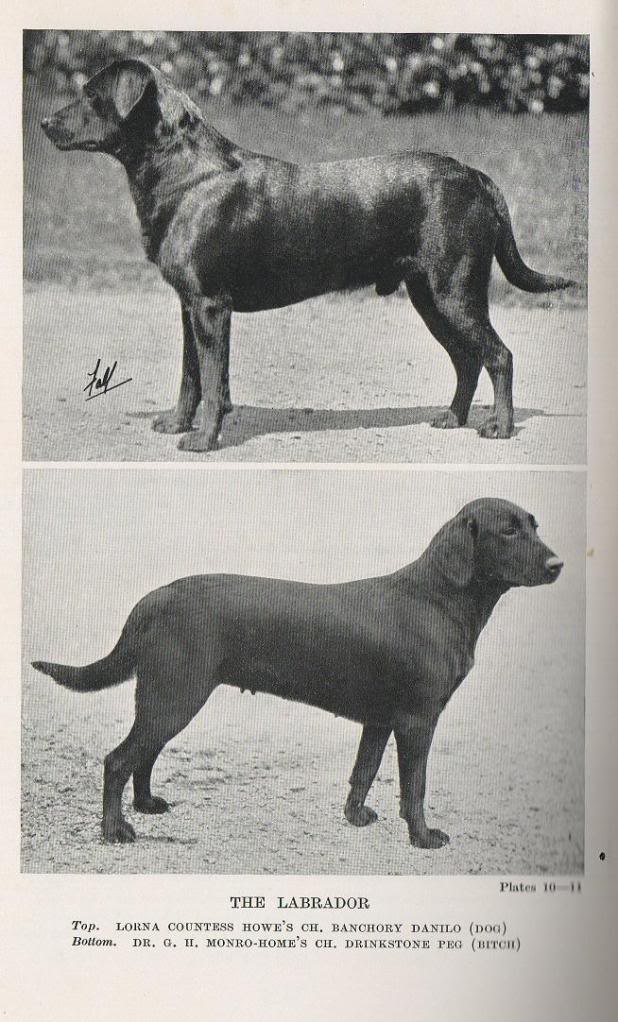

Until 1892 all the Labradors recorded were black, some still had the white markings. But in that year, two brown puppies were born on the Buccleuch estate in Scotland.

In 1899 we have the first yellow Labrador on record. His name was Ben of Hyde, owned by Major C. J. Radcliffe a neighbor of the Earl of Malmesbury. In 1871 Radclyffe had imported a dog from Newfoundland called Turk who sired Ben’s line that also included “Malmesbury Sweep”.

Ben was called Yellow although he was more butterscotch in color.

However the black dogs were still preferred as gun dogs being easier to see when ahead of the guns.

The Labrador Retriever was recognized by the Kennel Club (England) in 1903, and the American Kennel Club in 1917.

The Golden Retriever and the Labrador Retriever share a common ancestor, the St John’s Water Dog.

Golden Retrievers were originally included in the group flat coated retrievers, then for a time became known as Yellow Retrievers. They were derived from crosses between the Wavy (or Flat) Coated Retriever, the Tweed Water Spaniel, the Red Setter, and the Labrador.

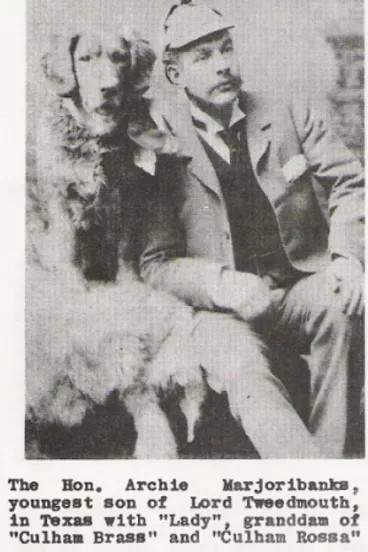

The Golden Retriever breed is attributed to Dudley Coutts Marjoribanks of Scotland who became the 1st Baron Tweedmouth.

While in Brighton in 1865, Marjoribanks bought a yellow Wavy-coated Retriever named Nous from a cobbler. It was believed that the dog had been used as payment to the cobbler by the gamekeeper for Lord Chichester. The dog was part yellow, and was therefore less valued than the all black ones.

The breed then known as the Wavy-Coated Retriever, now mostly known as the Flat-Coated Retriever, was believed to have come from a cross between a St. John’s and a Collie and/or unknown breed of retrieving Setter.

In the mid 1800’s they were Britain’s most popular breed and are still used today as working retrievers as well as family pets.

Wavy-Coated Retrievers were mostly black but some have been yellow, liver, or even black with a white tuxedo and boots just like a St. John’s.

The Tweed Water Spaniel was used by fishers on the mouth of the river Tweed in the English county of Northumberland close to the Scottish border. The village of Norham is famous for being the origin of the breed. The Tweed is now extinct and was similar to but probably larger than the American or Irish Water Spaniels of today although those breeds have a more curly coat.

The Tweed Water Spaniel is believed to have been a cross of locally bred water dogs with, you guessed it, the St John’s Water Dog. The Curly-Coated Retriever is another descendant of the Tweed.

Tweed Water Spaniels were brown otherwise known as liver colored.

The name Spaniel was originally used to describe dogs that were imported from Spain.

The Red Setter or Irish Setter originated in Ireland being selections from the older breed called the Red and White Setter. Originally the Red and White was preferred for hunting being easier to spot when crouching in tall grasses. The Red dogs were preferred as show dogs and pets.

It seems likely that the setter itself is a cross between a Spaniel and a Pointer and were bred for hunting on land. Setters had great eyes and were used to stand and point to potential prey.

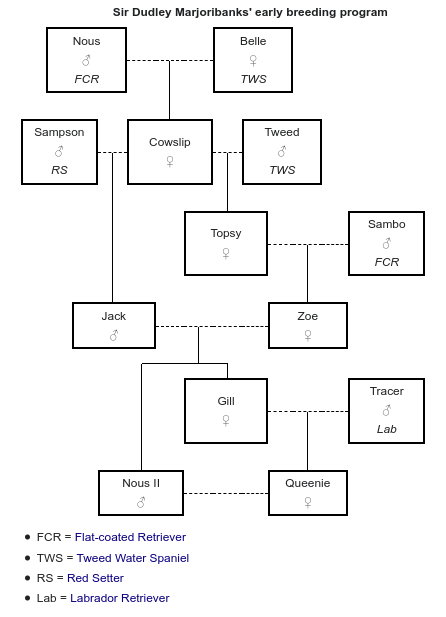

Sir Dudley Coutts Marjoribanks crossed his Flat Coated Retriever ‘Nous’ with a Tweed Water Spaniel dam ‘Belle’ producing a female ‘Cowslip’.

‘Cowslip’ was bred with a Red Setter ‘Sampson’ producing a male ‘Jack’.

‘Cowslip’ was also bred with another Tweed Water Spaniel ‘Tweed’ producing a female ‘Topsy’.

‘Topsy’ was bred with another Flat Coated Retriever ‘Sambo’ producing a female ‘Zoe’.

‘Zoe’ was bred back onto ‘Jack’ from the ‘Cowslip’ litter.

The resulting litter included a male ‘Gill’ and a female ‘Nous II’.

‘Gill’ was mated with a Labrador ‘Tracer’ producing a female ‘Queenie’.

The chart stops there so presumably ‘Nous II’ and ‘Queenie’ became the forbears of the Golden Retriever breed.

The result of the cross produced an ideal all-round water hunting dog, being able to both flush and retrieve game. The inclusion of setter in the bloodline may have increased the neck length making it easier for the dogs to keep their noses to the ground while running.

The name is ‘Golden’ because that is the prominent color, but as we know today their coats can range from almost white to yellow to butterscotch to liver, even rarely all black. Occasionally some have dots mainly on the snout and some have white patches on the chest showing their heritage. Otherwise there are no multicolored examples.

Marjoribanks kept primarily the yellow puppies (and a few blacks) to continue his line.

The first litter in 1868 was four yellow dogs called Cowslip, Crocus, Primrose, and (unconfirmed) Ada.

The “Golden Retriever” breed was recognized by the Kennel Club (England) in 1908 and the American Kennel Club in 1925.

The story would not be complete without that of the Chesapeake Bay Retriever, affectionately known as the “Chessie”. By now you will not be surprised that the Chessie is also descended from the St’ John’s Water Dog.

The dog was developed in the Chesapeake Bay area in Maryland as a waterfowl retriever. It is usually brown with a curly coat and is distinguished by it’s light amber eyes.

In 1807 a ship destined for Poole in England was shipwrecked in a storm. That ship carried salt cod and two St John’s water dogs to be sold as a breeding pair in England.

The crew fearing the worst drank the alcohol on board and became intoxicated. But before the ship sank they were rescued by a local vessel, the Canton, that was returning from England to it’s home in Chesapeake Bay.

The crew were dropped off in Norfolk in Virginia but the dogs were kept onboard having been bought for a guinea each by George Law, the rescuer and a nephew of the ship’s owner. The Canton then headed for Baltimore, Maryland.

The dogs were given the names ‘Sailor’ and ‘Canton’, after the rescuing ship. The male Sailor was described by Law as “dingy red” in color, bearing a short but very thick coat, the female Canton was mainly black.

Following is an account by George Law, first published in 1852:

Baltimore, Maryland – January 7th, 1845

My DEAR SIR,

In the fall of 1807 I was on board of the ship Canton, belonging to my uncle, the late-Hugh Thompson, of Baltimore, when we fell in, at sea, near the termination of a very heavy equinoctial gale, with an English brig in a sinking condition, and took off the crew. The brig was loaded with codfish, and was bound to Pole, in England, from Newfoundland. I boarded her, in command of a boat from the Canton, which was sent to take off the English crew, the brig’s own boats having been all swept away, and her crew in a state of intoxication. I found onboard of her two Newfoundland pups, male and female, which I saved, and subsequently, on our landing the English crew at Norfolk, our own destination being Baltimore, I purchased these two pups of the English captain for a guinea apiece. Being bound again to sea, I gave the dog pup, which was called Sailor, to Mr. John Mercer, of West River; and the slut pup, which was called Canton, to Doctor James Stewart, of Sparrow’s Point. The history which the English captain gave me of these pups was, that the owner of his brig was extensively engaged in the Newfoundland trade, and had directed his correspondent to select and send him a pair of pups of the most approved Newfoundland breed, but of different families, and that the pair I purchased of him were selected under this order, The dog was of a dingy red colour; and the slut black. They were not large; their hair was short, but very thick-coated; they had dew claws. Both attained great reputation as water-dogs. They were most sagacious in every thing; particularly so in all duties connected with duck-shooting. Governor Lloyd exchanged a Merino ram for the dog, at the time of the Merino fever, when such rams were selling for many hundred dollars, and took him over to his estate on the eastern shore of Maryland, where his progeny were well known for many years after; and may still be known there, and on the western shore, as the Sailor breed. The slut remained at Sparrow’s Point till her death, and her progeny were and are still well known, through Patapsco Neck, on the Gunpowder, and up the bay, amongst the duck-shooters, as unsurpassed for their purposes. I have heard both Doctor Stewart and Mr. Mercer relate most extraordinary instances of the sagacity and performance of both dog and slut, and would refer you to their friends for such particulars as I am unable, at this distance of time, to recollect with sufficient accuracy to repeat.

Yours, in haste, GEORGE LAW

Mr. Mercer, who owned Sailor, wrote that

. . . he was of fine size and figure-lofty in his carriage, and built for strength and activity; remarkably muscular and broad across the hips and breast; head large, but not out of proportion; muzzle rather longer than is common with that race of dogs; his colour a dingy red, with some white on the face and breast; his coat short and smooth, but uncommonly thick, and more like a coarse fur than hair; tail full, with long hair, and always carried very high. His eyes were very peculiar: they were so light as to have almost an unnatural appearance, something resembling what is termed a wail eye, in a horse; and it is remarkable, that in a visit which I made to the Eastern Shore, nearly twenty years after he was sent there, in a sloop which had been sent expressly for him, to West River, by Governor Lloyd, I saw many of his descendants who were marked with this peculiarity.

Sailor and Canton were bred with local hunting dogs along with water spaniels and maybe other St. John’s to eventually produce the Chesapeake Bay Retriever. There is no record of the two being bred together.

The Chessie became a very popular dog in the area being used for waterfowling, fishing, and even human rescue. They are a robust dog, physical and active, although not entirely suitable as pets.

Even today there is a statue of a St. John’s in Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum, it can be found on Google Street View.

In 1918 the Chesapeake Bay Retriever was recognized by the American Kennel Club.

* CAVEAT: while I believe the information presented here as fact to be true, I am not suggesting it is the whole story. The stories are centered around Canada, the US, and Britain because those countries use the English language as do I. There were many nationalities involved in fishing around Newfoundland and Labrador and it is likely that the dogs featured in activities in their home countries too.

NOTE: It is possible to trace the heritage of GDB produced Labradors right back to Beucleuch Avon from 1885.